Tablets are the craze at the moment. As with all tech crazes, there is a tendency to tout tablets as the ultimate device capable of doing everything, including spelling the demise of their less trendy brethrens. And if we have learnt anything from previous tech crazes, we need to be wary of such simplistic, blanket premises.

A tablet is designed primarily as a consumption device. It can be pressed to take on creation tasks of course, such as editing a document on the go. But it can’t perform as effectively as a “real” wordprocessor, attached to a real keyboard, on a large screen.

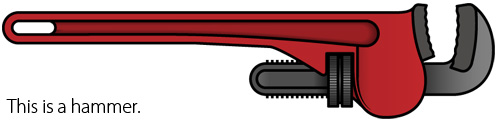

Logic says there has to be a penalty when we use the wrong tool for the job. A wrench function as a hammer at a pinch. But a hammer will be better. A pair of scissors can certainly cut up a steak, but a knife would be more appropriate at the dinner table.

The majority of the tech media seems to be consumers rather than prosumers. As such, there is a tendency to approach technology from a simplistic can-do/cannot-do perspective. Just because a nifty video editing app is available on a tablet will not enable it to replace a full-fledged editing workstation.

The real question is not so much whether a tablet can or cannot do, but how well it does it in a professional work context. What are the potential penalties on productivity? What about ergonomics? Or information security? What is the use context?

A university may deploy tablets to students to improve the access to information. But expecting students to actually write assignments on these tablets, even with attached keyboards, is folly.

A large corporation may use tablets to ease access to their central data stores. But trying to process/analyse datasets on a small slow tablet is ludicrous.

Tablets can certainly complement less fashionable computers. But to try and press them into service replacing computers may not be a smart move.